Report on the dementia situation in Kenya

Also see: Full Report on the Dementia Situation – Desk Reviews

MAPPING DEMENTIA CARE IN KENYA

Christine W. Musyimi1; Wendy Weidner2; Elizabeth M. Mutunga3; Levi A. Muyela1; Adelina Comas-Herrera4; Klara Lorenz-Dant4; David M. Ndetei1,5

1Africa Mental Health Research and Training Foundation, Kenya

2Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI), UK

3Alzheimer’s & Dementia Organization, Kenya

4London School of Economics and Political Science, UK

5University of Nairobi, Kenya

Citation: Musyimi, C., Weidner, W., Mutunga, E., Muyela, L., Comas-Herrera, A., Lorenz-Dant, K., Ndetei, D., Mapping dementia care in Kenya. Policy Summary. CPEC, London School of Economics and Political Science, London

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Inequalities in access to dementia care can be addressed through care planning at individual, community and policy levels in order to meet the needs of people living with dementia and their carers. The following key messages could be instrumental in achieving coordinated dementia care in Kenya:

- Develop a national dementia action plan and policy to implement a coordinated approach to dementia care

- Reduce stigma by increasing understanding and awareness of dementia among healthcare workers and members of the general public

- Improve dementia care pathways through coordinated service care delivery in health care settings, including training community health providers or non-mental health specialists to provide timely diagnosis and evidence-based mental health care

- Train health care workers and community members to support family carers in understanding dementia care

- Build research capacity in universities and colleges to generate evidence for dementia care including risk-reduction

- Work with the World Health Organization’s Global dementia Observatory to collect and monitor Dementia Specific data and improve inter-departmental collaboration (e.g. mental health and other non-communicable diseases sectors)

INTRODUCTION

Dementia is a chronic condition and the seventh leading cause of death among older people globally 1. By 2050, East and North Africa as well as Middle East have been predicted to have the highest growth in the number of people living with dementia 2. In Kenya, the ageing population is expected to double over the next three decades with an age-standardized both-sex dementia prevalence estimated to increase from 600 cases per 100,000 in 2020 to 660 per 100,000 cases in 2050, translating to 316% percentage change in the number of people living with dementia 2. Dementia care becomes complex as the disease progresses yet there is lack of literature and government policies that could inform dementia care pathways in Kenya. This policy summary is part of a larger in-depth desk review on dementia care landscape in Kenya 3 developed within the Strengthening Responses to dementia in Developing Countries (STRiDE) project implemented in seven middle-income countries (Kenya, South Africa, India, Indonesia, Brazil, Jamaica and Mexico) 4. The project (in Kenya, a collaboration between Ministry of Health, Africa Mental Health Research and Training Foundation (AMHRTF) and Alzheimer’s and Dementia Organization Kenya (ADOK)) examines current practices to support the development, implementation and evaluation of national strategies to deliver appropriate, equitable, effective and affordable dementia care.

Overall country context: Kenya has an estimated population of nearly 53 million people, with approximately 1.3 million (2.4%) over the age of 65 5. Kenya’s population is expected to reach about 91.6 million by 2050 and by then the share of older population will more than double, reaching 6.7% 5. The 2019 census revealed that 70% of the total population resides in rural areas with about half of the residents living below the poverty line resulting in a reduced focus on health care 6,7.

CURRENT DEMENTIA CARE LANDSCAPE IN KENYA

Dementia Policy in Kenya: There is no national plan/policy on dementia or mention of dementia in any policy document in Kenya yet. However, the Ministry of Health, responsible for dementia detection and management is actively working towards developing a National Dementia Plan for Kenya in collaboration with the World Health Organization, ADOK and AMHRTF.

Legislation/laws on rights of people with dementia and their carers: There is no legislation around safeguarding the rights of people living with dementia, however, Kenya ratified the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (‘CRPD’) in 2008 8. Subsequently the law was absorbed (Article 2(6)) in the Constitution of Kenya 2010. However, people with disabilities, including people with dementia, are still not able to enjoy the same benefits as other people 9. There are no other provisions for protecting the rights of people with dementia. The care and protection of older members of society bill, 2018; PART III provides for the prohibition, notification and register of abuse of an older member of society and PART VII indicates the manner in which matters concerning older members of society are to be tackled while taking into consideration the unique needs of such persons 10. However, this is not specific to people with dementia. There are currently no national or sub-national online accessible documents on standards, guidelines or protocols specific to dementia in Kenya.

Health care financing: The health care sector in Kenya is divided into the public sector, a private for-profit sector and a private not-for-profit sector. The sector gets funds from three main sources: direct payments/out of pocket payments (OOP) forms the highest proportion of health expenditure (30%); government expenditure (through taxation, employer schemes, health insurance, etc.); and donors 11. The private sector is mainly funded by donors through grants/programmes to NGOs, health insurance and out-of-pocket payments. The Ministry of Health estimates that 16% of people who are sick do not seek treatment due to financial constraints, while 38% of them must sell some of their assets or borrow in order to finance their medical bills 12.

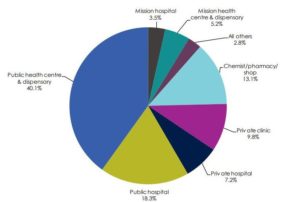

In 2013 (figure 1), there were marked differences in healthcare utilization between urban and rural areas, with higher use of public healthcare in rural areas (66.7% of all outpatient visits), compared to urban areas, where outpatient visits are equally distributed between the public and private sector. In rural areas, public health facilities are distantly located and on average, families travel a distance of 1-hour walk on foot (3km) which sometimes is a hindrance to uptake of health services 13.

Figure 1: Health care access in Kenya, source: Ministry of Health 201414

Public health care access in Kenya is facilitated by proximity to lower levels of care (dispensaries and health centres). However, unlike in public health care facilities where a structured referral process is followed to access services at higher levels of care i.e. referral hospitals within counties or at the national levels, private health care access is dependent on the ability to pay for the services and/or quality of services (e.g. comprehensiveness, responsiveness, caring, privacy) rather than proximity.

In 2018, Kenya only had 20.7 doctors and 159.3 nurses (enrolled and nursing officers) per 100,000 10, considerably lower than the minimum threshold recommended by the World Health Organization (average of 21.7 doctors and 228 nurses per 100,000 people) 15. Poor remuneration, understaffing, inadequate medical supplies and poor working conditions in the public sector has contributed to health care workers migrating to private clinics/hospitals or in urban settings 16. Health care in Kenya is financed from three main sources: direct payments/out of pocket payments (OOP) forms the highest proportion of health expenditure (30%); government expenditure (through taxation, employer schemes, health insurance, etc.); and donors 11. Half of the total health budget is allocated to the three referral hospitals and the remaining resources are allocated to the 47 counties and are based on a resource allocation formula that takes into consideration factors such as the population, poverty levels, land share etc 17. The private sector is mainly funded by donors through grants/programmes to NGOs, health insurance and out-of-pocket payments. The Ministry of Health estimates that 16% of the sick do not seek treatment due to financial constraints, while 38% of them must sell some of their assets or borrow in order to finance their medical bills 12.

The introduction of a Universal Health coverage (UHC) scheme is expected to increase access to health care services across all the 47 counties by 2022 and involves the removal of user fees at all public health facilities 18. The pilot phase only covers four counties (Kisumu, Machakos, Nyeri and Isiolo), representing about 5% of the Kenyan population. This means that, other than Makueni County (which has initiated its own UHC see case study below), the other 42 counties currently rely on NHIF (National Hospital Insurance Fund), the main health insurer in Kenya covering 19% of the population with other private insurers covering 1% of the population 19. Those who are not insured tend to have lower education, live in rural and remote areas, be unemployed and are more likely to be women 19.

| Case study 1: Toward Universal Health Coverage – Makueni County

Kenya’s devolution process that involved a referendum to split power between national and county governments has seen Makueni County being lauded by the World Bank and recognized as a model County in Kenya, due to the excellent public participation structures from the grass root level upwards. During the making of the 2018-2022 County Integrated Development Plan, more than 12% of the population within the County took part in public participation forums. This has provided an opportunity for the county residents to prioritize and own projects that are beneficial to them and those with the greatest impact; and promote quality improvement. Another initiative specific to the county is the implementation of its own universal Health Care Programme referred to as Makueni Care. This involves free health care services for those aged 70 and above and payment of an annual fee of Kshs. 500 ($5 US dollars) per family to cover both preventive and curative services within the County. Furthermore, the Makueni Gender Based Recovery Centre was established to enhance comprehensive management of Gender Based Violence (GBV) services and strengthen functional Referral mechanisms. Specifically, a safe shelter in one of the health centres and near a police station with a 15-bed capacity (8 for women and 7 for men) has been allocated for short-term placement of the most vulnerable survivors of GBV. In the County, persons with dementia are exposed to neglect and abuse 18 and defilement across all ages is often performed by family members/relatives and/or neighbor hence the need for a safe shelter. In terms of mental health care, clinicians in 20 primary health care facilities were trained by Africa mental Health Research and Training Foundation in 2016 to identify and treat common mental illnesses. The County’s achievements could be seen as a best practice blueprint that could be used as practical peer learning opportunities and scaled up in other counties. |

Dementia awareness and stigma: In Kenya, there is a lot of stigma surrounding dementia due to lack of knowledge and understanding. Following discussions conducted within the STRiDE project, many attribute symptoms of dementia to being cursed, bewitched, having annoyed the “gods” or failure to fulfil a certain obligation and as a result are being punished for their wrongdoing 20,21. Campaigns on dementia awareness are held on a continuous basis by ADOK depending on available resources. The STRiDE project has developed a group anti-stigma intervention with a social contact element to create awareness and reduce stigma among members of the general public in low-resource settings 22.

Dementia risk reduction: Currently the Ministry of Health in Kenya has no defined measures in place to monitor the number of people or indicators for dementia in the country. A person diagnosed with dementia is often seen at a mental health clinic in a hospital setup, however, mental disorders are often reported as aggregate data rather than by specific conditions 23, resulting in lack of evidence on diagnosis rates in the country. Between 1990 and 2016, there was an increase of 15.3% in deaths attributed to dementia 24. Whilst there is no national prevalence data on dementia 25, a regional study conducted in 20 health facilities in Makueni County by AMHRTF revealed that the rate of cognitive impairment using Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) was 1%, ranking second after depression among mental health problems 26. Increasing age, illiteracy, vascular disease and other non-communicable diseases, low-fiber diet, depression and genetic factors (presence of APOE-𝜀4 allele) have been identified as risk factors for dementia in two reviews on epidemiology of dementia in Sub-Saharan Africa and developing countries 27,28.

There is potential for substantial reductions in the number of cases of dementia due to improvements in education. Furthermore, an increase in understanding of dementia, improving inequalities in social and health care and creating awareness on the importance of healthy living through proper diet and exercise could potentially reduce the number of dementia cases2.Campaigns conducted by ADOK to create awareness on dementia care partly cover risk reduction such as encouraging exercise and good diet. The STRiDE Kenya anti-stigma intervention also covers some diet and exercise considerations for people living with dementia to live healthy lives.

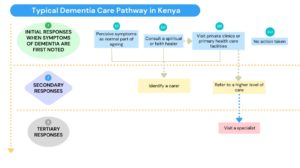

Diagnosis, treatment and care: People living with dementia in Kenya may find it difficult to follow a specific path to seek a diagnosis of dementia and post-diagnostic path because of lack of research evidence on recognized care pathways and existing support systems, and this may affect their future health plans. Currently dementia diagnosis and care ranges from non-specialists (traditional and faith healers, community health workers, relatives and friends, clinicians) to specialists (psychologists, psychiatrists, neurologists, geriatricians) and access depends on proximity to information (appropriate and inappropriate), services and affordability.

For those who are able to access higher levels of primary health care (referral county hospitals), dementia diagnosis is usually made by a medical officer, but as a secondary condition, affecting the rates of diagnosis. Specialists are scarce (particularly in rural areas), resulting in reliance on traditional and faith healers or clinicians who may not have received training or have expertise in dementia diagnosis and care 21. A summary of this care pathway is outline in figure 2.

Figure 2: Typical dementia care pathway in Kenya

There are no national or county guidelines in Kenya on dementia management except the adoption of the WHO mental health Global Action Programme Intervention Guidelines (mhGAP-IG) for use in managing priority mental illnesses (including dementia) in developing countries. However, this has not been rolled out in Kenya yet.

NGO support

Depending on the needs established by different organizations, some NGOs have collaborated with the Ministry of Health to fund research 29,30, create awareness on dementia 31 and focus on the needs of older persons in general 32. The STRiDE project has tested the feasibility of an anti-stigma intervention to create awareness on dementia using community health workers 33.

Dementia care and support

Primarily, dementia care takes place in home settings by family carers (spouse, parent or children and often female) or unorganized and unregulated domestic workers (paid informally in the home of caregiving relatives) 34. There is no dementia specific care provided in dispensaries and health centres. This means that referrals are often made if the community providers or health care workers are not able to manage the conditions. In primary care settings, with a mental health clinic within referral hospitals, treatment for dementia (diagnosis made at advanced stages) usually focuses on reducing symptoms and improving the quality of life of the person with dementia by engaging with their carers.

There are few residential care homes catering for people living with dementia. All the residential care homes available are private and they are mostly in urban centres 35. In the public sector the only residential care option available are hospital-based palliative care services where people with dementia and at advanced stages are taken if they cannot afford private residential homes.

Workforce

A multidisciplinary team (comprised of a physician, nurse, social worker) is key in providing holistic and collaborative care approaches to persons living with dementia 36. In Kenya, mental health training/courses for the health and social workforce do not specifically focus on competencies around dementia 37. Persons with dementia receive pharmacological treatment at the mental health clinic with the help of psychiatric nurses. This happens in 14 out of 47 (or 30%) county hospitals with a functional mental health unit 38 but only for those who are fortunate to receive a diagnosis. The concept of outpatient (community) social centres does not exist in Kenya.

Support for dementia carers

The informal provision of care by family members is considered as an obligatory role 39. However, family carers are neither registered nor recognized as part of dementia diagnostic services. Their role in terms of responsibility to their family member with care needs, is recognized in the care and protection of older members of society bill, 2018; PART III 59(f) which states that “Pursuant to Article 57 of the Constitution, every older member of society has the right to receive reasonable care, assistance and protection from their family and the State” yet and there is little to no focus on the quality of life of the carers.

The process of employing paid carers (domestic workers often referred to as house helps) for persons with dementia is unorganized and unregulated and informal (special arrangement between the individual [carer] and the family member) with only less than 10% having formal contracts 40. However, only a few families can afford these services.

Family carers in Kenya experience financial instability due to costs of treatment and living expenses. In addition, they struggle due to limited access to information and evidence-based care. Carers have also been found to experience burn out and stigma linked to misconceptions about the illness 41. Although not documented in Kenya, carers for people with dementia are often called “invisible second patients” due to the high rates of psychological morbidity and physical ill-health 42

Currently there is no specific support for carers, neither through monetary compensation from the government or other forms of formal support from health or social services 43 or through respite care. ADOK, however, offers ad-hoc training and monthly peer support group meetings (to share experiences) for carers of persons living with dementia.

Training and education of informal carers: The majority of carers feel inadequately trained for the skills they need to provide caregiving. Being the primary carer can impact significantly on all aspects of their lives, including a delay in educational progress or social activities outside the family. Carers may not look for employment because the needs of the person they support are too demanding to combine work with their care responsibilities. Carers in employment may face the risk of losing their job, limited promotional and training opportunities, and a reduction in retirement savings and Social Security benefits 44. There are currently no employment policies for unpaid/family carers in Kenya.

Dementia research and innovation: So far, there is no published document illustrating Kenyan government’s plan or proposed funding towards dementia research. The STRiDE project in Kenya, has been the first to involve people with dementia and their carers in the research development process 33,45,46.

RECOMMENDATIONS

These recommendations comprise actions that are needed to ensure the delivery of appropriate, equitable, effective and affordable dementia care. Formulating policies at national and county levels are a key first step towards improved dementia prevention, care, treatment and support systems so that people with dementia, carers and family have the highest possible wellbeing and functional ability 47. In order to achieve coordinated dementia care in Kenya it is salient to:

- Develop a national dementia action plan and policy to implement a coordinated approach to dementia care

- Reduce stigma by increasing understanding and awareness of dementia among healthcare workers and members of the general public

- Improve dementia care pathways through coordinated service care delivery in health care settings, including training community health providers or non-mental health specialists to provide timely diagnosis and evidence-based mental health care

- Train health care workers and community members to support family carers in understanding dementia care

- Build research capacity in universities and colleges to generate evidence for dementia care including risk-reduction

- Work with the World Health Organization’s Global dementia Observatory to collect and monitor Dementia Specific data and improve inter-departmental collaboration (e.g. mental health and other non-communicable diseases sectors).

References:

- World Health Organization. Dementia: Key facts. (2022). at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia

- Global Burden of Diseases 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Heal. (2022).

- Musyimi, C. et al. The dementia care landscape in Kenya: context, systems, policies and services. STRiDE Desk Review. (2022). at https://stride-dementia.org/desk-review/?country=kenya

- Comas-Herrera A, Docrat S, Lorenz-Dant K, Ilinca S, Govia I, Hussein S, Knapp M, Lund C, S. M. and the Str. team. In-depth Situational Analysis: desk-review topic guide. STRiDE research tool No.3 (version 2). (2021). at https://stride-dementia.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/STRiDE_Research_Tool_3.pdf

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, P. D. World Population Prospects 2019, Volume II: Demographic Profiles (ST/ESA/SER.A/427). (2019). at https://population.un.org/wpp/Graphs/1_Demographic Profiles/Kenya.pdf

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS). 2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census Volume I : Population By County and Sub-County. I, (2019).

- Nyakundi, C. K. et al. Health Financing in Kenya: The case of RH/FP. (2011).

- Government of Kenya. The Kenya Constitution, 2010. Kenya Law Reports (2010).

- The Open Society Initiative for Eastern Africa. How to implement article 12 of convention on the rights of persons with disabilities regarding legal capacity in Kenya: A briefing paper. (2013).

- Republic of Kenya. The Care and Protection of Older Members of Society Bill, 2018. Kenya Gazette Supplement No. 73 (Senate Bills No. 17) 333–363 (2018).

- Munge, K. & Briggs, A. H. The progressivity of health-care financing in Kenya. Health Policy Plan. 29, 912–920 (2014).

- Luoma, M. et al. Kenya Health System Assessment 2010. Heal. Syst. 20/20 Proj. 20, 1–133 (2010).

- Mugo, P. et al. An Assessment of Healthcare Delivery in Kenya under the Devolved System. (2018).

- Ministry of Health. 2013 Kenya Household Health Expenditure and Utilization Survey. (2014).

- Republic of Kenya. Kenya Health Policy 2014-2030. (2014).

- Ndetei, D. M., Khasakhala, L. & Omolo, J. O. Incentives for health worker retention in Kenya: An assessment of current practice. EQUINET 62, 29 (2008).

- Maina, T., Akumu, A. & Muchiri, S. Kenya County Health Accounts: Summary of Findings from 12 Pilot Counties. (2016).

- Kariuki, S. World Health Day: Universal Health Coverage – Everyone, Everywhere – Celebrating Kenya’s journey towards universal health coverage. Ministry of Health (2019).

- Kazungu, J. S. & Barasa, E. W. Examining levels, distribution and correlates of health insurance coverage in Kenya. Trop. Med. Int. Heal. 22, 1175–1185 (2017).

- Musyimi, C. W. et al. Perceptions and experiences of dementia and its care in rural Kenya. Dementia14713012211014800 (2021).

- Musyimi, C., Mutunga, E. & Ndetei, D. in World Alzheimer Report 2019: Attitudes to dementia 121–122 (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2019).

- Musyimi, C., Muyela, L., Mutunga, E. & Ndetei, D. in Global dialogue on LMICs: Reflections – The dementia landscape project, essays from international leaders in dementia (ed. World Dementia Council) 12–13 (World Dementia Council, 2022). at http://www.worlddementiacouncil.org/DLP/global-dialogues/LMICs

- Kiarie, H., Gatheca, G., Ngicho, C. & Wangi, E. Lifestyle Diseases: An Increasing Cause of Health Loss. (2019).

- Nichols, E. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 18, 88–106 (2019).

- Farina, N. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of dementia prevalence in seven developing countries: a STRiDE project. Glob. Public Health 15, 1878–93. (2020).

- Mutiso, V. N. et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of nurses and clinical officers in implementing the WHO mhGAP intervention guide: Pilot study in Makueni County, Kenya. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 59, 20–29 (2019).

- Olayinka, O. O. & Mbuyi, N. N. Epidemiology of dementia among the elderly in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2014, (2014).

- Kalaria, R. N. et al. Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia in developing countries: prevalence, management, and risk factors. Lancet Neurol. 7, 812–826 (2008).

- Mutiso, V. et al. Multi-sectoral Stakeholder TEAM Approach to Scale-Up Community Mental Health in Kenya: Building on Locally Generated Evidence and Lessons Learnt (TEAM). (2016).

- Africa Mental Health Training and Research Foundation. Welcome to AMHRTF. AMHRTF (2020).

- Alzheimer’s & Dementia Organization Kenya (ADOK). Training. ADOK (2019).

- HelpAge International. Terms of Reference for Development of Home Based Care (HBC)/Community care Package – Training Manual for the care of Older People in Kenya and Mozambique. HelpAge International(2019).

- London School of Economics (LSE). Strengthening Responses to Dementia in Developing Countries (STRiDE). STRiDE (2018).

- World Health Organization. WHO series on long-term care: Towards long-term care systems in sub-Saharan Africa. (2017).

- Achuka, V. The new age dilemma of caring for ageing parents. Daily Nation (2016).

- Galvin, J. E., Valois, L. & Zweig, Y. Collaborative transdisciplinary team approach for dementia care. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 4, 455–469 (2014).

- University of Nairobi. Department of Psychology. Department of Psychology (2019).

- Ministry of Health. Kenya Mental Health Action Plan 2021-2025. (2021). at https://publications.universalhealth2030.org/uploads/Kenya-Mental-Health-Policy.pdf

- Burr, J. A., Choi, N. G., Mutchler, J. E. & Caro, F. G. Caregiving and volunteering: are private and public helping behaviors linked? Journals Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 60, S247–S256 (2005).

- International Labour Organization. Planning for success: a Manual for domestic workers and their organizations. (International Labour Organization (ILO), 2017).

- Johnston, H. Caring for caregivers: challenges facing informal palliative caregivers in Western Kenya. Indep. Study Proj. Collect. 2684, (2017).

- Brodaty, H. & Donkin, M. Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 11, 217 (2009).

- Chepngeno‐Langat, G. Entry and re‐entry into informal care‐giving over a 3‐year prospective study among older people in N airobi slums, K enya. Health Soc. Care Community 22, 533–544 (2014).

- Collins, L. G. & Swartz, K. Caregiver care. Am. Fam. Physician 83, 1309 (2011).

- Breuer, E. et al. Beyond the project: Building a strategic theory of change to address dementia care, treatment and support gaps across seven middle-income countries. Dementia 21, 114–135 (2022).

- Breuer, E. et al. Active inclusion of people living with dementia in planning for dementia care and services in low-and middle-income countries. Dementia 14713012211041426 (2021).

- Breuer, E. et al. Beyond the project: Building a strategic theory of change to address dementia care, treatment and support gaps across seven middle-income countries. Dementia 0, 1–22 (2021).