DESK REVIEWS | 08.02.03. What are the social norms and traditions of family care? Are there gender roles associated with family care?![]()

DESK REVIEW | 08.02.03. What are the social norms and traditions of family care? Are there gender roles associated with family care?

We have information on informal care used by the general population, not specifically for people living with dementia. According to the first nationally representative study of older people published in 2018 (ELSI-Brazil), 94.1% of the care is provided by family members at home, of which 72.1% are provided by women (Giacomin et al., 2018). An integrative review conducted among Brazilian studies between 2011 and 2016 also revealed that the majority of informal carers of older people (not specifically carers of people living with dementia) are women (usually daughters), aged 56.3 years (on average), married, and who dedicated themselves exclusively to caring (Santos et al., 2017).

In Brazil, there is a social expectation that women (the first choice would be the spouse; and the second, a daughter or daughter-in-law) would be the primary caregiver. Care homes are not accepted by the general population due to stigma and poor regulatory systems of the quality of such care services (Camarano & Barbosa, n.d.). In addition, there is a very limited number of care homes which are public; the majority of them are private services which need to be paid for by the families. This contributes to the maintenance of unpaid care as the main source of care for older people nationally.

References:

Camarano, A. A. & Barbosa, P. (n.d.). Instituições de Longa Permanência para Idosos no Brasil: Do que se está falando? (pp. 479–514). Retrieved July 17, 2019, from http://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/bitstream/11058/9146/1/Institui%C3%A7%C3%B5es%20de%20longa%20perman%C3%AAncia.pdf

Giacomin, K. C., Duarte, Y. A. O., Camarano, A. A., Nunes, D. P., & Fernandes, D. (2018). Care and functional disabilities in daily activities – ELSI-Brazil. Rev. Saúde Pública, 52(Suppl 2). https://doi.org/10.11606/S1518-8787.2018052000650

Santos, D. F. B. dos, Carvalho, E. B. de, Nascimento, M. do P. S. S. do, Sousa, D. M. de, & Carvalho, H. E. F. de. (2017). ATENÇÃO À SAÚDE DO IDOSO POR CUIDADORES INFORMAIS NO CONTEXTO DOMICILIAR: REVISÃO INTEGRATIVA. SANARE – Revista de Políticas Públicas, 16(2). https://doi.org/10.36925/sanare.v16i2.1181

Taking care of aged parents is still a social norm of family care in Hong Kong. In general, it can be observed that the traditional Confucian notion of filial piety as a cultural norm still runs deep even in this modern and highly developed city. This provides adults children a motivation to embark on the caregiving journey. Yet, two local studies (Lee, 2004; Wong & Chau, 2006) describe and articulate that the filial values in the context of elderly care in Hong Kong are different and evolving from the traditional ones. Other than filial values, the provision of care by an adult child is also determined by their living arrangements, geographical proximity, and quality of relationship with the aged parent. It turns out that daughter usually becomes the carer, instead of the eldest son who is supposed to have the largest responsibility to take care of parents according to the traditional filial values (Lee, 2004). Moreover, carers have adopted some aspects of the filial norm, but not all of it, to suit their own experiences and actual circumstances in their everyday caregiving practices. For instance, instead of blindly following the wish of their parents, carers would challenge their parents while having their own considerations and making decisions during care provision (Wong & Chau, 2006).

In Hong Kong, when an older adult becomes in need of care, either his/her spouse or at least one of the adult children, if any, would take up the role of primary carer. Owing to the limited size of residence, adult children often live in another household nearby, instead of living with the parents in need. Moreover, live-in foreign domestic helpers and formal community care services are often utilised to assist in household chores and daily care. Regarding gender roles, females are more likely to be family carers. A recent study conducted by the author research team in 2018 to evaluate the Dementia Community Support Scheme (Wong & Shi, 2020) provides some demographic information of family carers of people with dementia in the community. Among 1385 primary carers, 66% are females, 27% are spouse of the person with dementia, 65% are children and 4% are children-in-law. In line with other local studies on family care, daughter is the most common type of family carer in terms of relationship.

Despite the family values and beliefs that maintain the provision of family care, it is important to note that the family structure in Hong Kong is changing. Due to the decreasing marriage rate and fertility rate, Hong Kong will inevitably face the challenge of reduced capacity of family in the provision of elderly care. In other words, the number of older adults without support from younger family members are expected to increase in the future. In fact, such a trend is already observed from the recent statistics on living arrangements provided by the Census (Census and Statistics Department, 2018b). From 2006 to 2016, the proportion of older adults living alone increased from 11.6% to 13.1%, those living with spouse only increased from 21.2% to 25.2%; and the proportion of households with older adults only hiring domestics helpers increased from 7.1% to 13.2%.

References:

Census and Statistics Department. (2018b). Hong Kong 2016 Population By-census – Thematic Report: Older Persons. Hong Kong Retrieved from https://www.bycensus2016.gov.hk/data/16BC_Older_persons_report.pdf

Lee, W. K.-m. (2004). Living arrangements and informal support for the elderly: Alteration to intergenerational relationships in Hong Kong. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 2(2), 27-49. https://doi.org/10.1300/J194v02n02_03

Wong, G. H.-Y., & Shi, C. (2020). Evaluation Study of the Dementia Community Support Scheme. Unpublished Manuscript. Department of Social Work and Social Adminstration. The Universtiy of Hong Kong. Hong Kong.

Wong, O., & Chau, B. (2006). The evolving role of filial piety in eldercare in Hong Kong. Asian Journal of Social Science, 34(4), 600-617. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853106778917790

Unpaid carers are those who provide care on a regular basis (i.e., family members) and are often closely related to the person with dementia. Spouses, sons, daughters, daughters-in-law and parents are the usual caregivers (informal caregivers) (Brodaty and Donkin, 2009). In traditional Indian culture, young adults of child-bearing age, earn and save for their children’s future. The assets gained are utilised for their children’s education, marriage expenses and subsequent costs associated. In this process they often fail to save for their old age. However, it is understood that their children will take care of them as they age. According to Gupta (2009), this understanding arises from the cultural concept of “dharma” (duty) (pp.1042), which emphasises upon this “moral duty” (pp.1042) of adult children to provide care and support for their elderly parents and in-laws. Traditionally, the son of the house marries and brings in a daughter-in-law, who will take care of the aging parents. In the event of frailty and ill health associated with old age, it is this social system that provides a background for age related decline and appropriate care arrangements. In this, she will be assisted by the extended family who will take turns to provide instrumental support, often in the form of assistance for hospital visits, respite for the primary caregiver and so on. This system has been the foundation of dementia care in India for many decades. However, demographic and economic changes are reshaping this familial system of care. In the absence of institutional support for the elderly, many families are struggling to maintain traditional caregiving roles (Srivastava et al., 2016).

References:

Brodaty, H., & Donkin, M. (2009). Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues inClinical Neuroscience, 11(2), 217–228. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19585957

Gupta, R. (2009). Systems Perspective: Understanding Care Giving of the Elderly in India. Health Care for Women International, 30(12), 1040–1054. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330903199334

Srivastava, G., Tripathi, R. K., Tiwari, S. C., Singh, B., & Tripathi, S. M. (2016). Caregiver Burden and Quality of Life of Key Caregivers of Patients with Dementia. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 38(2), 133–136. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.178779

Indonesia’s culture is characterized by strong family bonds and familial piety and, thus, caregiving for people with dementia is perceived as obligatory for family members (Hunger et al., 2019). In addition, the lack of available long-term care services leaves some families no other option but to take up the caregiving responsibilities. Kristanti and colleagues (2019) qualitatively compared the experience of family members caring for relatives with dementia and cancer in Yogyakarta. The main differences identified was that carers of people with dementia missed the loss of their previous relationship with the person they cared for and experienced difficulties in communicating with their relatives. In addition, carers of people with dementia blamed themselves as they believed they contributed to their relatives’ illness. They also found that in Indonesia, family carers invoke words such as “obligation” and “calling” to express reasons to be a caregiver for people with dementia (Kristanti et al., 2019).

Religion also plays a role in shaping the notion of obligation to give care, as some carers believe that good deeds on earth will be rewarded in the afterlife. For adult children, caring for their ailing parents is also a form of showing gratitude or reciprocity (Tatisina & Sari, 2017). Gender plays a significant role in caring for older people and people with dementia, with more women than men taking the role of carers (Tatisina & Sari, 2017).

References:

Hunger, C., Kuru, S. S., & Kristanti, S. (2019). Psychosocial burden, approach versus avoidance coping, social support and quality of life (QOL) in caregivers of persons with dementia in Java, Indonesia: A cross-sectional study. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.2.16801/v1

Kristanti, M. S., Effendy, C., Utarini, A., Vernooij-Dassen, M., & Engels, Y. (2019). The experience of family caregivers of patients with cancer in an Asian country: A grounded theory approach. Palliative Medicine, 33(6), 676–684. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216319833260

Tatisina, C. M., & Sari, M. (2017). The Correlation Between Family Burden And Giving Care for Dementia Elderly at Leihitu Sub-District , Central Maluku , Indonesia. 2(3), 41–46.

The Jamaica Gleaner (2017) reports that female-headed households represent the majority of mean household size compared to male-headed households. Additionally, female-headed households were also represented in the poorest quintiles (exact figures were not reported). Traditionally, parenting responsibilities and family care lies heavily on the female. In recent years, the female role has expanded to include meeting the financial needs of the family as well as the source of emotional support. Similarly, demographic profile from STRiDE Jamaica’s work package 4 of participants thus far and consistent with global literature, carers who participated were predominantly females (78.9%).

References:

The Jamaica Gleaner. (2017). Poverty climbed back to 21% in 2015. Available from: https://jamaica-gleaner.com/article/business/20171008/poverty-climbed-back-21-2015

Family members who provide care in Kenya continue to keep this role because of the fulfillment they get from giving care to their family member. They may also perceive providing care as a biblical mandate or maintain their role to avoid shame (Cappiccie et al., 2017). Additionally, unpaid care work is seen as a women’s domain while working for pay is considered a masculine task hence the high percentage of women assuming caregiving roles (Ferrant et al., 2014).

References:

Cappiccie, A., Wanjiku, M., & Mengo, C. (2017). Kenya’s Life Lessons through the Lived Experience of Rural Caregivers. Social Sciences, 6(4), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6040145

Ferrant, G., Pesando, L. M., & Nowacka, K. (2014). Unpaid Care Work: The missing link in the analysis of gender gaps in labour outcomes. OECD Development Centre: Issues Paper. https://www.oecd.org/dev/development-gender/Unpaid_care_work.pdf

Cultural norms towards care for older adults, children, and people with disabilities are still strong, with a large proportion of individuals stating that the family should have the main responsibility for caring. However, economic and social changes in the last years make these expectations increasingly difficult to meet (López-Ortega & Gutiérrez-Robledo, 2015). In a context with practically no publicly funded support for carers available nationally, especially for those caring for older adults and people with disabilities, families/unpaid carers provide the largest proportion of care in the country. Strong gender roles imply that within families, most care is taken up by women. In addition, women frequently take up most of other domestic activities (cleaning, washing, etc.) and increasingly, try to obtain some reconciliation between all these household responsibilities and their own individual development through education and work outside the household (Barrios Márquez AY & Barrios Márquez, 2016; Pedrero Nieto, 2004). As a result of the demographic transition and often perceived as a last-resource option, an increasing number of men have been observed to provide care for their spouses (Giraldo-Rodríguez et al., 2019; Nance et al., 2018).

References:

Barrios Márquez AY, & Barrios Márquez, O. (2016). Participación femenina en el mercado laboral de México al primer trimestre de 2016. Economía Actual, 9(3), 41–45.

Giraldo-Rodríguez, L., Guevara-Jaramillo, N., Agudelo-Botero, M., Mino-León, D., & López-Ortega, M. (2019). Qualitative exploration of the experiences of informal care-givers for dependent older adults in Mexico City. Ageing and Society, 39(11), 2377–2396. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X18000478

López-Ortega, M., & Gutiérrez-Robledo, L. M. (2015). Percepciones y valores en torno a los cuidados de las personas adultas mayores. In L. Gutiérrez Robledo & L. Giraldo (Eds.), Realidades y expectativas frente a la nueva vejez. Encuesta Nacional de Envejecimiento. (pp. 113–133). Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Nance, D. C., Rivero May, M. I., Flores Padilla, L., Moreno Nava, M., & Deyta Pantoja, A. L. (2018). Faith, Work, and Reciprocity: Listening to Mexican Men Caregivers of Elderly Family Members. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(6), 1985–1993. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988316657049

Pedrero Nieto, M. (2004). Género, trabajo doméstico y extradoméstico en México. Una estimación del valor económico del trabajo doméstico. In Estudios Demográficos y Urbanos (Vol. 19, pp. 413–446). https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/312/31205605.pdf

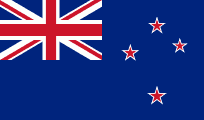

NZ is a multicultural country so social norms and traditions tend to vary between the different ethnic groups. As already outlined in part 8, those providing care are predominantly female.

The LiLACS NZ study, a longitudinal study of Māori and Non-Māori New Zealanders of advanced age, interviewed primary carers of participants about aspects of caregiving (Lapsley et al., 2020). Their findings included:

- Carers were more often women, particularly female spouses (because of their longevity and usually younger age), and children (because sex role conventions make it more likely that women will care for parents and parents-in-law).

- Males were cared for over a longer period and receiving more hours of care overall.

- Compared to Non-Māori, Māori received more hours of informal care and their carers were younger, more likely to be offspring, more likely to live in the same household and more likely to be of different ethnicity.

Those from Pacific cultures feel an obligation and responsibility to care for their elderly at home (Tamasese et al., 2014) and this is reflected in the lower proportion of Pacific people in aged residential care. An excerpt from Pacific Perspectives on Ageing in New Zealand highlights some of the challenges faced:

“What both the Elders and the younger people agreed on was that the care of Elders was simpler, supported, and possible within a communal village context. The Elders said that if they were carrying out the same responsibility at home in the Pacific the village structure would support the care of Elders better than the nuclear household living arrangements of New Zealand. In the New Zealand context if each household or family is caring for their own Elders, the pressures grow if there are inadequate familial, government or community supports” (Tamasese et al., 2014).

References:

Lapsley H., Hayman K. J., Muru-Lanning M. L., S. A. Moyes, Keeling S., Edlin R., et al. (2020). Caregiving, ethnicity, and gender in Māori and non-Māori New Zealanders of advanced age: Findings from LiLACS NZ Kaiawhina (Love and Support) study. Australas J Ageing. 39(1):e1-e8. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12671.

Tamasese K, Parsons L, Waldergrave C. (2014). Pacifc perspectives on ageing in New Zealand Wellington The Family Centre. Available from: https://www.massey.ac.nz/massey/fms/Colleges/College%20of%20Humanities%20and%20Social%20Sciences/Psychology/HART/publications/reports/Pacific_Elders_NZLSA_2014.pdf?6A68389EA6EAB37148E4AE22BA963822.

South Africa is largely a patriarchal society, whereby care is framed as a social practice and places women at the primary location of care within the family/community (Sevenhuijsen et al., 2003) and is viewed as a socially imposed occupation (Gurayah, 2015).

References:

Gurayah, T. (2015). Caregiving for people with dementia in a rural context in South Africa. South African Family Practice, 57(3), 194–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/20786190.2014.976946

Sevenhuijsen, S., Bozalek, V., Gouws, A. and Minnaar-Mcdonald, M. (2003). South African social welfare policy: An analysis using the ethic of care. Critical Social Policy, 23(3), 299–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/02610183030233001