DESK REVIEWS | 07.01.09. How do people with dementia access long-term care?![]()

DESK REVIEW | 07.01.09. How do people with dementia access long-term care?

We do not have a clear path for long-term care for people living with dementia specifically. But it is likely that this first access will be through primary healthcare units in the public services, and they will provide the long-term care together with the family. We have only few long-term institutions for people living with dementia or other conditions in the public sector, so we may consider that this does not exist. A small proportion of people may access philanthropic long-term care institutions. The private LTC sector is growing, but it is extremely expensive.

In Hong Kong, older adults including people with dementia must go through the Standardised Care Need Assessment Mechanism for Elderly Services to access subsidised long-term care service. The mechanism was implemented from November 2000 by the Social Welfare Department (Social Welfare Department, 2020i). Under the Mechanism, an internationally recognised assessment tool, the so-called Minimum Data Set-Home Care (MDS-HC) is adopted to ascertain the care needs of the elderly and match them with appropriate services. People in need can contact Social Welfare Department or social services providers for assessment on eligibility of subsidised long-term care services. The individuals opting for long-term care provided by the private sector, for instance residential care service, can contact the service provider directly.

References:

Social Welfare Department. (2020i). Standardised Care Need Assessment Mechanism for Elderly Services. Retrieved from https://www.swd.gov.hk/en/index/site_pubsvc/page_elderly/sub_standardis/

Few families who can afford the few long-term care services available for dementia in India, provide this care (out-of-pocket care) through hiring paid carers or using day-care centres or residential facilities (ARDSI, 2010).

References:

Alzheimer’s and Related Disorders Society of India. (2010). THE DEMENTIA INDIA REPORT 2010: Prevalence, impact, cost and services for dementia. New Delhi. Available from: https://ardsi.org/pdf/annual%20report.pdf

We were unable to identify relevant information. We searched via Medline, PubMed, GoogleScholar, Factiva, news, and Neurona.

No data was sourced.

Access is through the UHC and within general health settings or in non-governmental residential homes. There is currently no government funded long-term care in Kenya. Admission into the private residential home depends on the ability to pay for the services by the person or the family members and does not require approval of a health care provider (National Gender and Equality Commission (NGEC), 2016).

References:

National Gender and Equality Commission (NGEC). (2016). Audit of residential institutions of older members of society in selected counties of Kenya. National Gender and Equality Commission Headquarters. Nairobi, Kenya. https://www.ngeckenya.org/Downloads/Audit%20of%20Residential%20Homes%20for%20Older%20Persons%20in%20Kenya.pdf

Mexico does not have a publicly funded national long-term care system. However, care is being provided in different ways. First, unpaid informal care by family members is the main source of care and in some cases, especially when economic resources are available with the support of domestic paid workers. To our knowledge, there are only 4 long-term care (care homes) private institutions in the country that are focused exclusively on people with dementia. While (for-profit and non-profit) private care homes usually have as their main requirement for entry that the older adult is “functional and independent”, those who develop dementia will usually remain under their care, while others will make them return to the care of a family member. As a result, most older people with dementia, while receiving care in LTC institutions, will receive sub-standard care or care that is not optimal as the majority of managers and carers are not trained, nor the institutions equipped to provide dementia care and management.

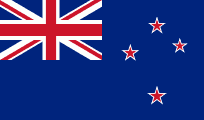

Access to long-term care is coordinated through the local NASC agency (see part 3).

Within the private sector, long-term care arrangements can be purchased, for example, assisted living, frail care, convalescence, as well as old age care (nursing/retirement homes) where they can buy or rent accommodation and are responsible for the full cost of their stay. There are 8 registered residential care facilities in the public sector, with eligibility restricted to the frail and destitute (see discussion under Part 3). Long waiting lists and constrained resources (see Part 2) despite eligibility, create an inequitable situation where access to long-term care are usually confined to the minority who can afford it, while most South Africans rely on home-based care provided by an unpaid carer (usually a female family member) (Sevenhuijsen et al., 2003). Furthermore, older persons with dementia are often not accepted for residential care as well as denied admission to hospitals for fear of bed-blocking (Kalula & Petros, 2011; Patel & Prince, 2001), and are also sent home because of a lack of awareness and understanding of dementia amongst healthcare workers where dementia is seen as a normal part of ageing and that nothing can be done with regards to treatment (Kalula & Petros, 2011).

References:

Kalula, S. Z., & Petros, G. (2011). Responses to Dementia in Less Developed Countries with a focus on South Africa. Global Aging, 7(1), 31–40.

Patel, V., & Prince, M. (2001). Ageing and mental health in a developing country: who cares ? Qualitative studies from Goa, India. Psychological Medicine, 31, 29–38. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/8896/600da12a3c3c4b8cbb55ce3c9a8bd8cc6d6e.pdf

Sevenhuijsen, S., Bozalek, V., Gouws, A. and Minnaar-Mcdonald, M. (2003). South African social welfare policy: An analysis using the ethic of care. Critical Social Policy, 23(3), 299–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/02610183030233001